IQ tests: what are they truly about? How do experts use them? And are IQ tests really a bad idea, or can they genuinely benefit you with things like learning the English language?

Definition, Purpose, and Types of IQ Tests

It can be difficult to resist taking a free IQ test online. Although these tests are timed and might be unpleasant, who wouldn’t want to discover in private just how intelligent they are? After all, they mimic real-world situations where we frequently must analyze information and find quick solutions to issues. Fortunately, you can access the resource here, which explains timed IQ test tactics.

A test called the “Intelligence Quotient” assesses your level of, well, intelligence. Your intellectual capacity, mental agility, and ability are all measured by an IQ test. This covers concepts such as rational thinking, math abilities, information retention capacity, linguistic skills, spatial relations, and problem-solving abilities. IQ tests have existed since the turn of the 20th century.

In the past, an IQ test determined your “mental age” by a few metrics. Your IQ score was calculated by dividing this by your chronological age and multiplying the result by 100. Your IQ would then be compared to the “normal” or “average” levels for each age group.

Tests these days provide more information on intelligence than just a single score. For instance, children between the ages of six and 16 typically take the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC). In addition to the conventional “IQ score”, there are five other scores that are produced, each of which examines a child’s performance in a different cognitive domain. These results, or “indexes”, are:

• Processing Speed Index

• Verbal Comprehension Index

• Visual Spatial Index

• Fluid Reasoning Index

• Working Memory Index.

Acquiring language skills allows us to interact with a diverse range of individuals, viewpoints, and cultural practices. It’s also said to enhance our physical appearance. But does it improve our cognitive capacities—that is, our capacity to reason, learn new things, comprehend the feelings of others, be creative, or retain information?

Under the direction of Professors Bencie Woll FBA and Li Wei, a British Academy-funded project examined the body of research supporting the advantages of learning a language to any degree of fluency for cognitive, academic, and age-related purposes, as opposed to bilingualism.

Cognitive Agility

A large amount of research indicates that bilingualism and cognitive flexibility—which is represented by the capacity to switch between languages—are related. The data, however, is contradictory and complicated when it comes to the connection between language acquisition and our capacity to control our behavior mentally. It seems that immersing oneself in the process of learning a new language enhances mental and attentional abilities.

It has been demonstrated that multilingual individuals frequently display higher levels of compassion and a global perspective. Researchers have documented the feeling that some people have when speaking their second language—that they are a “different person”. But we’re unable to determine exactly what causes what. Or is curiosity about and openness to various ethnicities an outcome of learning a language? Are people with a global mentality more likely to aspire to study a language and flourish in it?

On the other hand, there’s compelling evidence that acquiring a language fosters innovation in language use. Learning a second language improves one’s primary language fluency, creativity, and creative flexibility. We need further investigation to understand how this varies by age and gender as well as the learning strategy. This could be caused by the cognitive actions connected to learning a new language, such as the desire and versatility to change needed to do language shifting, or the strict study and practice involved in language learning.

Does Having (Fluid or Crystallized) Intelligence Make It Easier to Learn English?

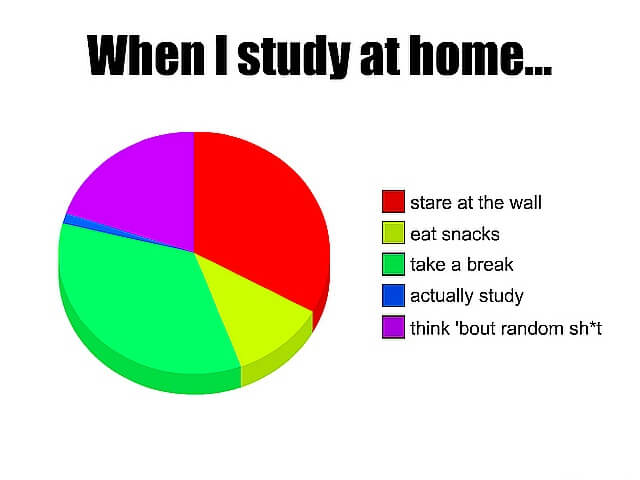

There’s ongoing debate concerning the connection between learning and intellect. Nevertheless, the rate of change regarding the English scores wasn’t predicted by either intrinsic drive or IQ testing’s fluid intelligence. These results add to the increasing amount of evidence suggesting that there may not be as strong of a correlation between academic long-term learning rate and intelligence as has been previously thought.

A capacity to absorb knowledge has been closely associated with most measures of intelligence from the early days of intelligence studies, and this association persists today. The present study investigated this widely held belief that intelligence, especially Gf (fluid intelligence), is intimately linked to learning within the framework of acquiring a foreign language. There’s a severe dearth of empirical evidence on this premise in the field of foreign language learning.

As a result, British-American psychologist Raymond Cattell postulated a strong correlation between Gf and learning rate when it came to the issue of developing academic skills, particularly learning the English language (Cattell, 1987). Schweizer and Koch (2002) expressly assume that learning explains the correlation between Gf and Gc (crystallized intelligence) in their reworked version of Cattell’s investment theory.

There’s little doubt in the empirical literature that intelligence scores, as determined by IQ tests, are a reliable indicator of academic ability. Less is known, however, about the usefulness of typical intelligence tests in evaluating learning capacity in the sense of quicker learning rates than is generally believed. According to a different perspective, intelligence scores—whether they be Gf or Gc, or g (general intelligence)—reflect the outcome of lifetime learning, a particular type of growing expertise that coincides with abilities required in educational settings (Grigorenko & Sternberg, 1998; Sternberg, 1999). According to this theory, intelligence is a product of learning processes rather than a reliable indicator of how well those processes work.

The intuitive link between intelligence and learning was therefore disproved when several early studies revealed no correlation between various intelligence indicators and gain scores in learning series. Such analyses are still relatively uncommon, nevertheless, since these investigations evaluate the correlation between learning and intelligence scores using growth curve studies.

Cognitive Ability’s Significance in the Learning of English Language

The acquisition of a first (or second) language is significantly influenced by cognitive abilities. Before we move on to examples, let’s explain what role cognitive abilities have in learning the English language as a first and second language separately.

Learners of Second Languages

In autumn 2021, there were projected to be 5.3 million English language learners in American schools, or nearly 10.6 percent of the total population. Over a billion people are thought to be English language learners worldwide. Over 750 million individuals speak English as a second language globally. Approximately 375 million people learn English as a second language; two or more languages are spoken by 60% of the world’s population. Thus, there’s a tremendous incentive to acquire a second language.

Learning a second (or other) language is often a different process than learning a first language, and an individual’s underlying cognitive skills may help—or hinder—the learning process in sometimes underappreciated ways. We’ll go over some of the difficulties associated with picking up a second language, as well as the role executive and cognitive processing play in second language acquisition.

Learners of First Languages

By the time they are six months old, babies have begun to identify the pronunciations of the language or languages that are being spoken around them. As a result, they are only able to learn those sounds and nothing else. Thus, it should come as no surprise that if we wish to talk without an accent, we would be far more successful in learning a language from a young age.

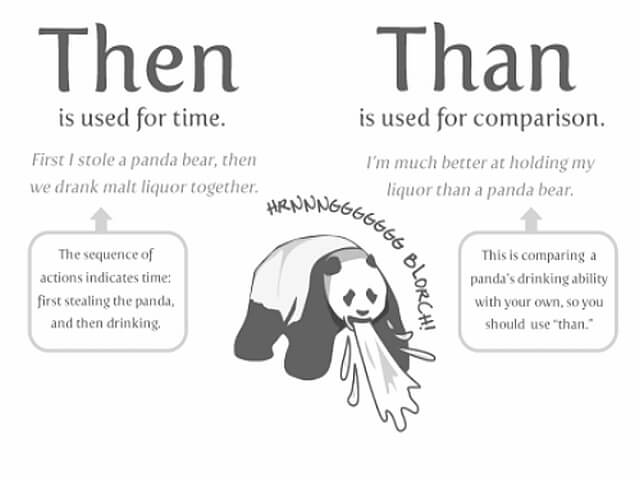

While younger people seem to pick up their first language easily, older kids and adults who are trying to acquire a new language are aware of how challenging it may be. However, not every facet of learning a language is equally challenging. After childhood, pronunciation is the hardest to learn. However, there’s a benefit to studying grammar early on, although this benefit varies greatly depending on the features of the language in question. When it involves vocabulary, there’s significantly less benefit to early acquisition.

Learning a Foreign Language and Cognitive Skills

Now let’s look at some instances of how cognitive abilities are crucial for learning a second (or other) language.

- Sensory memory, which is where language’s meaningful sounds, or phonemes, are recognized.

- The rules of language, such as how to form a plural and how to construct a past-tense verb, in addition to the exceptions to those rules, are stored and retrieved in long-term memory.

- One of the three primary executive functions, working memory, is where we store information while we comprehend it. It’s also a crucial component of conscious processing and is involved in all facets of comprehension, but it may be especially important so early in the learning process when a learner depends more on translation.

- One of the three primary executive functions is inhibition control, which is a mental operation that allows us to eliminate word candidates and choose a word from the target language instead of our automatic default word.

Are IQ-High Individuals Good Language Learners?

The answer is yes, however, that isn’t as significant as you may believe. Higher-IQ individuals often process and retain knowledge more quickly and effectively than lower-IQ individuals. The IQ test essentially measures that.

Learning anything, including languages and other skills like computer literacy, science, and even sports, depends on a variety of elements, including aptitude, dexterity, and interest, in addition to IQ. Therefore, those who have high IQs make excellent language learners because language isn’t the kind of thing that someone with a high IQ can memorize, unlike solving math problems or learning nation capitals for geography class.

There’s no denying that someone has a high IQ if they pick up the language and course material rapidly. However, if a person learns more slowly, it’s impossible to determine their intelligence. Do they lack extracurricular practice, are less experienced with language learning, lack confidence, have difficulty pronouncing new sounds, have poor social skills, or don’t have time to study outside the classroom? They can have gaps in important vocabulary or grammar because they were placed at a level that is too high for them. Additionally, many engineers excel in language skills related to syntax and organization, but struggle with language skills related to spontaneity and productivity. There are also many cultural elements.

Conclusion

Given high IQs, learning the desired language is gradual and laborious and can’t be accelerated. Practically speaking, high IQs can aid language learners in generalizing language forms and structures and in identifying recently learned words and structures, but they can’t accelerate language acquisition on their own. To put it another way, having a high IQ can aid in language acquisition, but not language itself.

To put it briefly, language is not learned; rather, it’s acquired gradually through practice, exposure to the target language, and appropriate methods and tools.